The Royce Mission is a key plot point of my first book ‘Fire Eye’ and deserves a separate article to explain the background. During early 1942 when British, Dutch, Australian and American forces were suffering one defeat after another, it was an attempt to strike back at the Japanese to boost morale and perhaps slow their relentless advance in thePhilippines.

The official history of the USAAF describes the Royce Mission as follows, ‘But one load of bombs could count for little in the final check up and some of the participants questioned whether the results justified the extraordinary effort required. Others returned with a memory chiefly of gallant men who had serviced their planes on Mindanao - men who already knew their doom. For this was the last major attempt to fly across the far-flung battle lines to their aid.’

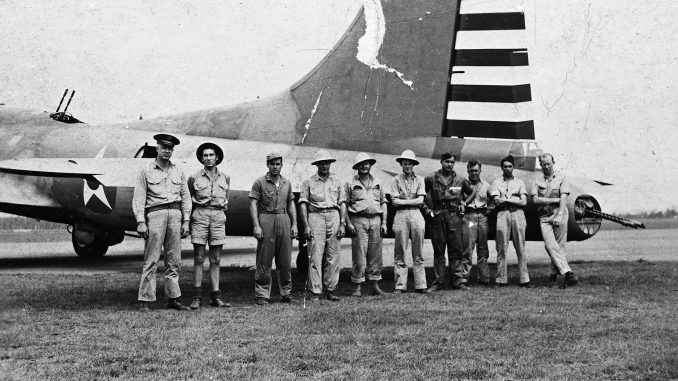

At the time it involved the longest ever flight of a strike force against an enemy. Some long range deployment of aircraft had been trialled by the Americans pre-war but none matched the challenge of the Royce Mission. Flying out of Darwin to hastily arranged fields in unoccupied Philippine territory, the Royce Mission (named after its commander, old army cavalryman Brigadier General Ralph Royce), consisted of a mixed force of three B-17’s and ten B-25’s against Japanese shipping and ground targets, some of which were former American facilities. Results of the hastily assembled mission turned out to be better than expected. However, enemy forces were too strong and Royce led the twelve surviving aircraft back to Australia just as General ‘Jimmy’ Doolittle was about to embark into the history books. Following the publicity generated by his famous raid onJapan, the Royce mission faded into obscurity.

In late March 1942, Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright, commanding the besieged troops on Bataan andCorregidor, radioed a plea to General Douglas MacArthur for bombers to clear a path for supply ships blockaded in the Philippine Visayan Islands. MacArthur ordered the commander of the Australian based Allied Air Forces in the southwest Pacific, Lieutenant General George H. Brett, to proceed despite Brett’s protests that such a mission was impossible.

If the distance wasn’t daunting enough, 4,000 miles (6 400 km) of enemy controlled air space and sea separating Manila from Australia’s northernmost air base at Darwin, Brett’s command was paralyzed by an air of defeatism pervading the early months of World War 2. In the wake ofJapan’s early conquests, a flood of refugee military personnel inundatedAustralia. There was little with which to arm them, especially the pilots who managed to escape. The only Australian aerial assets included Wirraway trainers and other outdated aircraft.Hudsonbombers acquired earlier from Americahad potential but numbers were limited. The only other available aircraft were a handful of worn out B-17’s that managed to escape south and a few American P-40 fighters.

Brett had access to a pool of officers who could lead the mission. Given circumstances there was really only one choice, Ralph Royce. The West Pointer had served with the 1st Aero Squadron in the 1916 Mexican Punative Expedition against Pancho Villa. In World War I, he received the French Croix de Guerre for flying the first reconnaissance mission over enemy lines.

In 1930, Royce was awarded the prestigious Mackay Trophy for guiding the 1st Pursuit Group over a long distance test flight through freezing temperatures fromMichigan to Washington State. Four years later, Royce endured blizzards and ice to pilot a B-10 bomber on an experimental expedition led by then Lieutenant Colonel Hap Arnold from Washington,D.C., to Alaska.

Even with all of Royce’s experience with long flights and long odds, even he couldn’t magically summon an air fleet during the desperate times of early 1942, however someone in Australia could.

As a teenager inArkansasin 1917, Paul Gunn was caught running moonshine. A wise judge offered him a choice - go to jail or join the service. Gunn chose the navy and his career as a Chief Petty Officer and carrier pilot unlocked talents in mechanics and aviation that would become legend. By the time theUnited Statesentered World War 2, Gunn had retired from the navy and was in the Philippines with his family managing Philippine Airlines. In one of MacArthur’s better decisions, he was called out of retirement with a captain’s commission and orders to shuttle VIP’s and supplies using the airline’s twin engine Beechcraft light transports.

When Manila fell to the Japanese in January 1942, Gunn’s wife and four children were interned. Gunn became obsessed with Japan’s defeat and his family’s freedom. Nicknamed ‘Pappy’, the bourbon loving aviator travelled all over the southwest Pacific, wearing a pair of shoulder holstered .45 automatics and usually surrounded by a cloud of cigar smoke. He motivated colleagues and civilians with salty language that today would be regarded as bullying. He exhausted men half his age pulling double duty assembling A-24 Dauntless dive-bombers, flying combat missions over Java and running supplies to the embattled Philippines. One flight on March 20 1942, earned him a Distinguished Flying Cross.

While in Melbourne looking for machine shops to service American transports, he came across two dozen B-25 Mitchell bombers of the Netherlands East Indies Air Force sitting idle with no pilots to fly them. Gunn despised the Dutch as he felt American forces had done a disproportionate share of the fighting in Java and the discovery left him furious.

He had recently arranged a transfer to the 3rd Bombardment Group, still waiting delivery of aircraft from the United States. He flew to the group’s base at Charters Towers in north Queensland to meet his commanding officer, Colonel John ‘Big Jim’ Davies. While Davies was frustrated by the lack of aircraft, he initially objected to Gunn’s suggestion to grab the B-25’s. Two days later, following orders from Far East Air Force Advance Headquarters in Brisbane, Davies decided to snatch the Dutch bombers and when caught, simply claim he had taken the wrong aircraft.

Davies, Gunn and 22 other pilots then flew to Melbourne. Using paperwork authorizing the pickup of the 3rd Bomb Group’s aircraft, they flew away with twelve Dutch B-25’s. By the time they stopped at Brisbane to refuel, complaints had caught up with them. Gunn cajoled a duty officer and continued on to Charters Towers in the early morning hours of April 3. Protests by the American and Dutch ambassadors failed had no effect. The Dutch were destined to meet Gunn again as while the aircraft were being serviced, the Norden bombsights were found to be missing. Gunn flew back toMelbourne to secure them. A standoff with a Dutch supply officer ended when Gunn reportedly drew both his .45’s to support his requisition. Even Jed would struggle to mount a winnable argument against two Colt’s waved around with passion but then, he would have sided with ‘Pappy’ anyway and avoided the confrontation.

On April 6, Davies and Gunn received urgent orders to report to theMelbourne headquarters of the U.S. Army Forces inAustralia. Expecting disciplinary action, they were instructed to meet with General Royce a couple of days later. Royce told them that to increase the B-25’s range, extra fuel tanks would be installed. The bombers would fly to thePhilippines and operate out of secret fields on Mindanao still in friendly hands. Also present was Captain Frank P. Bostrom, a B-17 pilot from the 19th Bomb Group, which would be teaming up on the mission. Bostrom knew the route as only weeks earlier he had flown General MacArthur and his family from Mindanao to Australia. Only six B-17 bombers were available but Royce got three.

Ultimately 10 B-25’s would participate in the mission, one with Pappy Gunn at the controls. When the expedition landed inDarwinon the morning of April 11, bad news awaited them. Bataanhad surrendered but they continued with the mission anyway. With fuel gauges falling toward empty, the bombers were about to be swallowed by a storm swirling above Mindanao when a hole appeared in the cloud cover and they located Del Monte airfield. On the ground rifle shots signalled an air raid and sent men scrambling for cover as the bombers landed before the remaining Del Monte personnel, none of whom had ever seen a B-25.

Bataan’s fall meant there was no longer a need to attack around Luzon. The Royce mission had come to attack and that’s what they did, making aggressive, strikes against Japanese shipping as well as naval and air installations until they ran out of bombs and fuel.

They were the first Allied bombers to strike the Japanese and inflict real damage, as well as shock. Back at Del Monte, Japanese bombs sent Royce running to a dugout five times and even helped put out a fire. More enemy planes, as well as ground forces, were undoubtedly on their way. As smoke mushroomed over Cebu and Davao, the general decided it was time to leave the Philippines. He ordered the B-25’s home. They also evacuated civilians, reporters and military personnel MacArthur had cleared to leave the islands. Gunn learned a lot about tactics from the mission. The way to fight with a B-25 was to get right down on the water with the ships and blow them to hell.

The Royce Raiders departed Australiain secrecy and initially returned to fanfare. Royce received a priority telegram from U.S. Army Chief of staff General George C. Marshall, ‘Good work stop Congratulations.’ The April 16 New York Times called the raid ‘the most spectacular aerial thrust of the Pacific War.’ There were press conferences and popping flash bulbs, as well as a ceremony during which Royce and Davies were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

News of the ‘Doolittle Raiders’ April 18 strike against targets in Japan reached the world two days later, banishing the accomplishments of Royce and his men, first to the back pages, then to obscurity. Yet the effects of Royce’s mission were felt into 1943 and beyond, perhaps affecting the Pacific War more extensively than the Doolittle Raid. Both raids showed that while the Americans were down, they were not out of the fight.

Royce’s men navigated a record long distance deployment, operated for two days deep behind enemy lines, sank eight ships, shot down five aircraft, inflicted significant damage on Japanese installations and personnel, suffered no casualties and brought home all but one, of their invaluable aircraft. Those immediately tangible results paled in comparison to the raid’s short and long term effects at the individual, local and theatre level. The mission rescued nearly three dozen important individuals from certain captivity or death, reinvigorated MacArthur’s command and signalledAmerica’s determination to the subjugated people of the Philippines and also to anxious Australians. At that time, resolve and loyalty were words well understood by Americaand its allies.

Following the mission, ‘Pappy’ Gunn went to work reconfiguring B-25’s and A-20’s with the innovations in ordnance and tactics he conceived over the Philippines. These evolved into the deadly techniques of skip bombing and low level strafing that would bring astonishing results at the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March 1943 and deliver devastating attacks on Japanese strongholds, with Rabaul a major target. Gunn was finally reunited with his family after the liberation ofManilain early 1945.

Ralph Royce would receive promotion to Major General in June 1942 and serve in Europe, the Middle East and the United Statesuntil the war’s end. But, as his Distinguished Service Cross citation supports, in the early days of the Pacific conflict at a time when defeatism was the accepted doctrine of the day, Royce and his raiders left their mark through their ‘determined combative spirit of aggression… heroism, and extraordinary achievement.’

The Royce mission provided a perfect basis for ‘Fire Eye’, an action / adventure thriller set in the wilds of northernAustralia. An extra aircraft was added to the mission that would be flown by Alex’s grandfather. It was her desire to find his aircraft that led her to Jed Mitchell and the adventure that would lead to a confrontation with her past abuser.

Australia’s frontier history and outback themes add a little more flavour to the story.